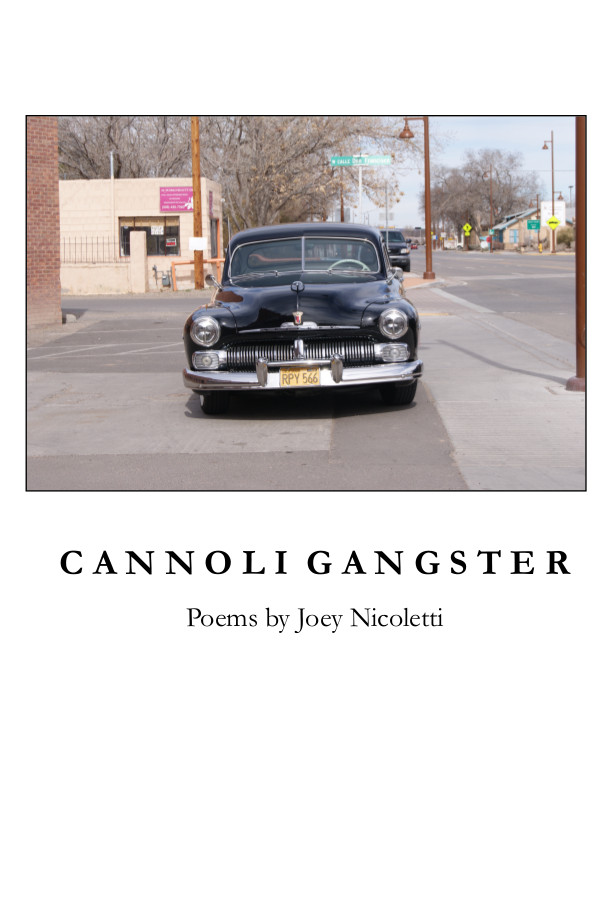

Cannoli Gangster

by Joey Nicoletti

Poetry

WordTech Communications/Turning Point, 2012

$ 19.00, 100 pages

ISBN: 978-1936370887

Steeped in the memory of a past that keeps slipping through its fingers, Joey Nicoletti’s Cannoli Gangster takes us on a wild ride across America, from Queens and Long Island, New York, to the Midwest and Southwest, and ends up back at “My Sister’s Wedding Reception,” among characters Nicoletti both loves and holds at arm’s length, as he comes to terms with his own personal odyssey. His is a constant process of evaluation and re-evaluation best summed up in a stanza from the poem, “Knapsack Moon”:

And now I’m like a dishwasher,

foaming with scratched forks and knives.

Tomorrow morning they will be sorted and put away,

and at night they will stab and stain their way back

into my blue, gap-toothed mouth.

Those forks and knives — those memories — keep jabbing and poking Nicoletti’s consciousness throughout the volume.

The fact that this poem is dedicated to Nancy Pelosi only underscores the fun.

Consisting of five parts, Cannoli Gangster begins with the poem, “Why I Don’t Speak Italian,” a story of first-generation Italian-Americans assimilating into American society with the effect of denying an aspect of his heritage to the speaker. Thus begins a section about being Italian-American in Twentieth Century New York, the era when Puzo’s Godfather captured the nation’s attention. (One of the book’s epigraphs comes from The Godfather film: “Leave the gun. Take the cannolis,” the character Peter Clemenza, portrayed by Richard Castellano, says after a mafia execution.)

The implicit violence that characterizes the poems of this section is also Godfather-esque. In “Green Monster” the speaker glimpses “the head of a switchblade/rising from my father’s shirt pocket/like a shark fin.” In “The Cook-Out,

At midnight I will wake up

in my aunt and uncle’s bedroom

to the sounds of gunshot and breaking glass

in the littered streets, the sharp aroma of onions

mingling with cigar smoke.

In “Maintenance,” the boy jumps into his friend Gina Falcone’s GTO, and “My bony hand waved goodbye/as we sped past the stop sign/with bullet holes in the letters/clusters of rust in the corners.”

But just as the title Cannoli Gangster suggests, there’s a sly sense of humor at work in these poems as well, notably in the poem called “When Italian-American Grandmothers Rule the World.” The fact that this poem is dedicated to Nancy Pelosi only underscores the fun.

The poems in the second section continue the theme of Italian-Americana in the mean streets of New York, including the eponymous poem, a sad short poem whose opening two lines tell you all you need to know: “It was another Tuesday, another afternoon of eating/what was in the refrigerator for dinner.” A sense of lawlessness pervades the poem, an otherwise quotidian tale of eating cannolis with his cousin Lenny, but with so much more, unstated, going on underneath, a family fraying at the edges, held together only by the violence always bubbling just below the surface.

So is it any wonder that the poet escapes to the heart of the heart of the country? But — does he ever truly escape? Part Three, the middle section, of Cannoli Gangster is a long, lyrical prose piece entitled “The Wrath of Khan” with the telling observation early on: “As I get older, the people I meet often ask why I left New York, and I’ve always replied that the main reason was to return.” Still, this middle section, which does involve a return to the scene of the crime, as it were, takes us to Santa Fe (where he meets his wife) and Lincoln, Nebraska, among other places, before we wind up on a flight back to LaGuardia for a reunion with old friends. This section (this poem) is named for a Star Trek film, with the revealing observation, toward the end of the piece, in a flight of fantasy about watching that movie with his father that the point is “To boldly go where no one cares,” a spin on the cult series’ signature theme, “to boldly go where no man has gone before,” an observation that reveals the poet’s ambivalence about returning at all. (Not that he has any choice, though, does he?)

...the book ends on an endearing note, really, despite the violence and chaos at the heart of the full tale...

Part Four involves the heartbreak of the poet’s parents’ divorce, as the fraying edges finally give way and the family is set loose in its own orbit — boldly going where no man has gone before, indeed. The poem “Red Ears” ends with the poet fiddling with the air-conditioning in his mother’s car as they drive back from visiting new post-divorce friends, the vent obviously defective, “destined to be out of place, just like my family.” In “Mexican Opera” the poet impulsively wrecks his mother’s record album and later observes: “I began to feel better because I had taken my frustrations out on someone else instead of dealing with them directly.” This whole situation may be summed up by Uncle Angelo in the poem, “Flash-a-Roni,” when, lit up by the flames of Chianti, he expounds

about how everything’s a revision —

the characters we read about and love,

the pasta we ate for dinner...

For the poet is coming to terms with the illusory stability we often take for granted, as children, families solid as oak, now washed away with the rest of our illusions about who we are, what we aspire to be, our “roots” and our basic rootlessness. To his credit, Nicoletti does not hammer us over the head with these speculations and conclusions: they are powerfully there for us to experience, and besides, yeah, ultimately, “no one cares.”

Thus, we wind up pretty much where we began, at “My Sister’s Wedding Reception”:

I sat at the same table as my father, who had

one hand on his girlfriend’s thigh

and the other on a 7 and 7...

Of course, there’s been a lot of water under the bridge in the meantime. Again, to his credit, Nicoletti comes to no conclusions about any of this. And in fact, the book ends on an endearing note, really, despite the violence and chaos at the heart of the full tale, seated there at the table at his sister’s reception with his dad and his recently divorced cousin Bobby:

But the stories.

Within seconds Bobby has begun a new one

about the time he auditioned for the role of

Hannibal Lector;

careless of failure;

careless of facts getting in the way of his tale,

making Barbara and everyone else laugh

the green sequins off her dress.