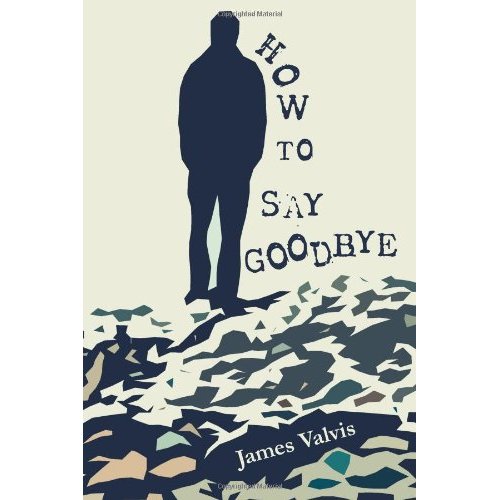

How to Say Goodbye

by James Valvis

Poetry

Aortic Books, 2011

$ 12.99, 192 pages

ISBN: 978-0978798338

James Valvis is a prolific poet. You see his work everywhere. He is about as ubiquitous in the small press as Lyn Lifshin or Robert Cooperman. Coming across one of his poems in a journal or online is like an opportunity to get a shot of wisdom, a perspective on life that is both useful and entertaining. As the title of this collection of poems suggests, How to Say Goodbye is a manual for dealing with heartbreak and life’s other curveballs. Not that there are ever any clear directions, but Valvis’ recipe calls for a heaping helping of dignity and a good sense of humor. The essential guideline may be found in the poem, “Live Fire Exercise” about a guy in army boot camp: The part that wins keeps his head down, keeps crawling.

Take the title poem. A man receives a call from his wife’s former lover, asking where she is. She’s with another man now, but the husband at least tries to be a friend while disentangling himself from her life. The narrator has a sense of ironic distance that gives us the clue to how to behave. He keeps his head down, keeps crawling. In poem after poem we find characters who blindly stumble into trouble and have nobody to blame for their predicament but themselves, and the paradox is that they are the innocent; they are often the victims, often merely collateral damage.

The collection is divided into three parts, “So Long,” “Farewell,” and “Godspeed”: clearly there’s a choice at work here in how to present the poems thematically, though not all of them deal with parting ways or breaking up. Sometimes, in fact, there’s a sort of annealing going on, as in the second poem of the collection, “Lifting,” in which a weightlifter initially gives the cold shoulder to an out-of-shape new gym member, sharing a private joke with his spotter at the speaker’s expense, only to come to a mutual respect with the out-of-shape speaker by poem’s end. But even this could loosely be construed as a leave-taking from cruelty. Still, How to Say Goodbye, the title, resonates with a sort of melancholy that is evident throughout the poems, even when they are humorous. There’s a way to cope with disappointment, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be anything like triumph. Keep your head down, keep crawling.

This melancholy that saturates Valvis’ poems frequently has to do with the romantic awareness of the impermanence of the things of this life, the inevitable decay and death of things to which we become attached; sometimes this awareness overwhelms the speaker of the poems, in the midst of general gaiety. “The Man in the Clock,” “The Old Film,” “At Cape Disappointment Lighthouse I Come to Terms with My Mortality”: yes, life is a constant act of saying goodbye to the things and the people we hold dear in this life.

Paul Kareem Tayyar notes in his foreword that the characters in Valvis’ poems are right out of the short stories of Raymond Carver, beat, blue collar men and women whose lives are so messy you want to flinch when you look at them, have to make a conscious effort not to turn your head away from them. Unreliable, alcoholic fathers, faithless depressed wives, ungrateful children, belligerent assholes. Especially poignant are the poems that involve the speaker’s father. Usually this character is a cruel, abusive alcoholic who puts the “dysfunction” into the dysfunctional family — “Company,” “Dad’s Brief Career as a Musician,” “Hail,” “Halo of Smoke,” “The Absentee Fathers,” “Relapse Incident”: these are only a few of the titles involving a father whose erratic behavior scars his children, his loved ones, the people around him.

But Valvis’ poems are full of humor, too. Sometimes you really do burst out laughing and sometimes it’s a sly wink that makes you smile. The poem, “Committed,” that ends the second part, is a great example:

Committed

Ex-wife, we’re divorced

almost twenty years after

just two years of marriage,

our divorce lasting ten times

longer than our marriage

and still going strong.

So we couldn’t commit

to our commitment but

you must admit, ex-wife,

we’ve been very committed

to the end of our commitment.

Maybe at twenty years

we should meet again and renew

our vow to quit on each other.

You can sleep around some

and I’ll fake not knowing.

Then I’ll buy you a ticket

to wherever it is I’m not

and you can tell me again

I put the hell in hello

and I can tell you again

you put the good in goodbye.

Or take the short poem, “Breasts”:

Breasts

All my life I loved breasts,

and now that I have them,

my wife wants me to diet.

These poems are funny even as they reveal an underlying sadness. In both, the speaker is resigned, as the speaker of Valvis’ poems is throughout the book, without being bitter, without regret of any sort. He keeps his head down, keeps crawling.

Many of Valvis’ poems are unrelieved by stanza breaks, sometimes several pages of verse without a break between lines. This suggests the sustained narrative impulse at work throughout this book. Valvis is a masterful storyteller, but his stories are not prose. They have the concentration and imagery of all good poetry, even if they do not always have the appearance of metrical lyrics. There are exceptions, of course. Valvis’ poems about his daughter are always tender and protective. “My Daughter Crying Becomes a Natural Disaster” exemplifies all of this:

My Daughter Crying Becomes a Natural Disaster

First the lips quiver

quakes parting the fault

of her pink mouth

now nostrils flaring

caves collapsing

in on themselves

then comes the blink

two eyes closing

like a double eclipse

as twin rivers

flood the deserts

of her cheeks

To read James Valvis’ poems is to feel as though you know the writer, that you and he are friends, that you go way back together: that both of you are keeping your head down, both of you are crawling.