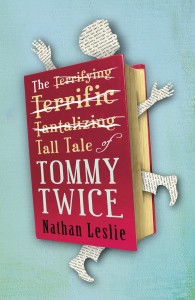

The Tall Tale of Tommy Twice

by Nathan Leslie

Novel

Atticus Books, 2012

$ 14.95, 204 pages

ISBN: 978-0984040506

From the title of Nathan Leslie's new novel, The Tall Tale of Tommy Twice, you can already tell you're going to be reading a whimsical story full of magic and exaggeration worthy of Mark Twain or Washington Irving. Yet the premise, an orphan on his own at the mercy of dubious relatives, is straight out of Charles Dickens, whose narratives also had the force of fables.

“Twice” is the name the narrator, Thomas, has chosen for himself, though his father's name was Jakoby. The name does not seem to have any significance about the destiny or identity of the narrator, though multiplicity is a theme that characterizes him, his fate, as he goes sequentially from one of his mother's sisters to the next over the course of his childhood. Multiplicity is also a characteristic of the ending, a sort of postmodern metanarrative pastiche.

It's not clear if Tommy's parents are still alive — to us or to Tommy. In tall tale fashion, Tommy starts the story of his childhood at the age of two in a time and landscape that seems both vague and familiar. He begins with his life with his grandmother, Gaga, at her remote mountaintop home on “Pike's Peak,” only, this is not that Pike's Peak, but still a place that seems to be in the American West.

He loves his grandmother, a no-nonsense disciplinarian, but when he reaches the age of five and needs to go to school she sends him to her daughter Tess, in “Boomtown,” which also has a vaguely western feel. Tess may be the most exaggerated of all the characters in this “tall tale,” with a voluminous mass of red hair in which she stores a whole inventory of items, including, “a dead chicken, a small pillow...an umbrella, curtains, a folding chair, a card table,” and many other things both large and small, living and dead.

Multiplicity is also a characteristic of the ending, a sort of postmodern metanarrative pastiche...

Tess has two good-for-nothing sons, Stump and Hose, and a sketchy husband named Rusty, a trucker who is away from home for months at a time and consumes his weight in food every time he returns, the description of which is classic “tall tale.” When things inevitably fall apart in Tess's household, Tommy moves on to the sister named Penny, who lives in “the city.” (All place names and locations are vague and dreamy, as befits the tall tale.) She is likewise weird in her own way — as are Chelsea and Beth, the other two sisters, and a woman named Marta with whom he lives for a time, whom he met on the bus ride to Boomtown when he was first going to live with Tess. In all of these settings, Tommy is consistently “the good boy,” trying to fit in, trying to please his hostesses, an Oliver Twist or David Copperfield kind of kid, or one of the orphans in a John Irving novel.

Leslie's characters are all memorable and distinct, from his grandmother and aunts and ne'er-do-well cousins and uncles to even the more incidental ones such as Willie the boatman (“I'll have to come back this way to hear the rest of your stories, young sir.”) and Marta's backbiting co-workers in the town of Misery. They are all vivid and eccentric. The only “normal” character, in fact, is Tommy, the orphan, a self-described “good boy.” We trust his voice, but then in the end even he cautions us that he is a liar - a teller of tall tales, indeed!

This novel feels like it could go on and on, a big, sprawling picaresque narrative, but Leslie cuts it short after Tommy finds the elusive sense of “family,” for which he has been yearning for all these years, with the sister named Beth on “Bear Lake Island,” an enchanted isle like something out of the land of the lotus-eaters, pure “tall tale.” Only, Tommy discovers this feeling of being in a family, a real “home” - the opposite of the orphan loneliness that has plagued him throughout his life - is hollow and illusory. He decides to flee the idyllic life on Bear Lake Island. In a concluding chapter appropriately called “The End,” Leslie provides a series of alternate endings in which Tommy a) goes to an orphanage, pursues a life there and becomes the new orphanage director; b) returns to Gaga, goes to school, gets married, has a conventional life in the suburbs; c) seems to reunite with his birth mother in a hospital setting in which his limbs have been amputated; d) becomes a dumpster-diving skidrow bum, and finally, e) in a voice that may be Leslie's and not Tommy's after all, reflects on the inexact, misleading nature of language, of story, of narrative, to bring into question that whole idea of a narrative arc with a beginning, middle, end, meaning, all-embracing conclusions.

Thus, The Tall Tale of Tommy Twice may resolve itself to a larger question about narratives generally: What isn’t a “tall tale,” finally? What story, description, narrative isn’t ultimately a flawed misrepresentation of something organic, something living? Event rendered dead by language. Words: the basic raw material of any tall tale, inherently flawed.

Such an observation may not be sufficient to hang a novel on, and I prefer to think of The Tall Tale of Tommy Twice as the tall tale it is for the first 90% of the book, full of vivid, quirky, eccentric characters and magical, jaw-dropping incident, driven by a sly sense of humor and a marvelous feel for the absurd, and related in such a way as to capture the naive innocence of a young boy. (Tommy tells us at the very start that he is writing this as a grown man looking back on his childhood.) Any one of the alternate endings was just fine for this reader, but I did wish the story had gone on for, say, another thousand pages: a truly entertaining read.