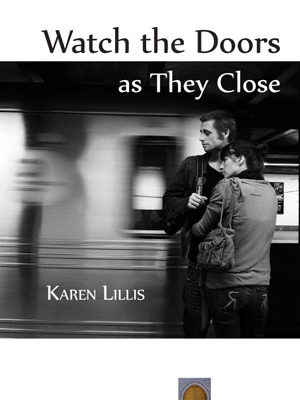

Watch the Doors as They Close

by Karen Lillis

Novella

Spuyten Duyvil Novella Series, 2012

$ 10.00, 90 pages

ISBN: 978-0-923389-87-1

Karen Lillis’ gem of a novella is written in the form of a diary by an unnamed female over the course of three weeks in December, 2003. It is not a diary in the sense of daily entries that recount the events of the day. In fact, we know almost nothing about her activity during this time except that on December 24 the narrator, who lives in New York City (Brooklyn), boards a train for Washington, DC, presumably to spend the holidays with her family, though nothing’s ever mentioned, and on December 30, the final entry, she is about to board the return train.

Watch the Doors as They Close is a soul-searching exploration of an all-consuming love affair that has recently ended. In fact, three days into the journal, December 14, the narrator writes, “Anselm and I broke up a week ago — a week ago today, in fact. On the phone, after he’d already left New York again to return to his mother’s house in Pennsylvania.”

Indeed, the journal begins, “This is the story of Anselm. The story of Anselm as told to me.” It’s this introspective inquiry that makes the choice of the diary form so compelling. A diary is written for oneself, an attempt to make sense of one’s life. To get a bead on her own life, the narrator must come to terms with her lover, the man with whom she shared a room for the past three months in an often tempestuous affair.

Anselm Vaughan Brkich-David entered the narrator’s life in a bar at 2:00 A.M. one night when she was “shit-faced drunk.” If not the classic “love at first sight,” the meeting was so intense that they wanted to see each other again, and thus began the affair. Only, who is Anselm? This consumes the narrator for the duration of the novel, and in the end, despite the cataloging of his likes and dislikes, his travels, background, behavior, loves, obsessions, he becomes even more remote, more shadowy, less certain. We watch the doors as they close over her certainties about the validity, the authenticity of their relationship. (Who was that masked man?)

Anselm grew up in the dirt poorest area of Appalachia, in Pennsylvania coal mining country near West Virginia. His father committed suicide, tormented by the effects of black lung disease. His mother was crazy, his sister remote. Yet Anselm, a musician and composer, managed to escape to Oberlin College and thence on a grand Bohemian tour that brought him to Paris, Vienna, and ultimately to New York. Anselm’s life seems to be marked by the women with whom he is serially involved, Meredith and April and Sandra and many others who appear indistinguishable to the reader but who are vividly individual in the narrator’s mind. This is a diary, after all, not a novel in which characters are developed for a plot. Indeed, the way the women blend into one another adds up to the narrator’s own doubts about how genuine her own relationship with Anselm was.

The narrator is a writer, and Anselm tells her she is “the first writer he ever met who had something to say.” This has got to be self-affirming, heady. Anselm even offers to collaborate with her on an opera, he writing the music, she the libretto, and off the narrator goes into a fantasy about Edna Saint Vincent Millay. But is Anselm ultimately just another bullshit artist? The reader wonders this as the narrator fears it may be true. By the end of the diary she is comparing moments when they were “real” with each other and when they were being fake, and she even wonders if Anselm is a scam artist or worse, some sort of psychopath.

Still, the conviction remains that there must have been some sort of “spiritual” legitimacy at work. It wasn’t a complete mirage, was it? “Sometimes I felt like his emotional stenographer, like he was looking back over his whole life and dictating it to me. I would wonder about his attraction to writers. Did he want to hand his life story to someone else who might make sense of it?”

But of course really, it’s her own life she is trying to make sense of, isn’t it?

This is a diary, after all, not a novel in which characters are developed for a plot...

All of this is written as an intense groping toward the truth. The narrator was raised as a Catholic and has a nostalgia for the confessional, its therapeutic effects. “I suppose the strong instinct to write the tell-all comes from Catholicism, I thought upon waking today,” she writes on December 15. “The concept of a Confessor is so specific, and doesn’t get replaced with anything else in society once you leave the Church.” So in writing this confession, she tries to come to an understanding, which is the true nature of any diary, after all. “I want the challenge of someone who cares enough to tell me the absolute truth.”

We do get glimpses of the diarist’s life in quick asides that give an insight into the feverish way her brain is trying to process the affair. “I just got back from walking over to Bushwick to donate books to a new women’s library,” she writes on December 16. “It reminded me of the story Anselm told me about the project he and a friend of his started to get Penguin to donate books to schools in Appalachia.” This is a story about the good Anselm, constantly at war in the narrator’s head with the bad Anselm, a conflict which is ultimately never resolved, can never be resolved. All she can do, finally, is watch the doors closing...

By novel’s end, the reader does get a sense of closure, not in the way a plot reaches a resolution, but in a kind of resignation in the narrator’s one. Not a small accomplishment for this kind of narrative. Bravo, Karen.