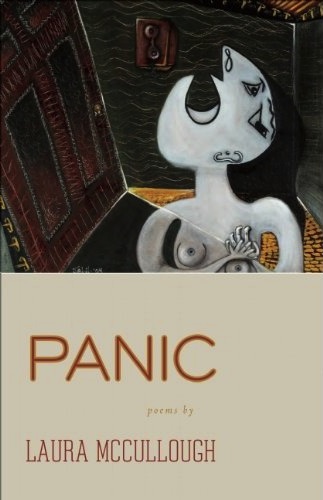

Panic

by Laura McCullough

Poetry

Alice James Books, 2011

$ 15.95

ISBN: 978-1-882295-84-5

There have to be boundaries, some limits, protest the children of a man whose behavior, though not criminal or destructive, does not conform to conventions, in the poem “Cancer Man,” in Laura McCullough’s new collection, Panic. This is precisely what these poems address, the limitations of our control over our fates, our private grief and longing. Set at the edge of the Jersey shore — Red Bank, Asbury Park, the Oxygen Bar, place—names both familiar and exotic — these poems focus on the intimate struggles of ordinary people. The dubiously heroic figure of the lifeguard is prominent throughout. Who else but a lifeguard at a pool can circumvent tragedy, after all, or has even a smidgen of control? Especially in these shore towns, so “overcharged and fecund.” (“What Breathes at the Oxygen Bar”) As in a dream, a handful of calamities recur in variation — a drowning, a pool mishap, an injury at a construction site. But the underlying drama involves how we cope, react: how we change.

The three parts of Panic — “Panic,” “Virus” and “What Breathes” — are variations on the same theme. In the first poem, “Dissolution and Assemblage,” we encounter the injured man, his leg “trapped/between the girder and the cement.” (“He could have been a lifeguard,” we learn.) The scene dissolves into chaos and panic, only to find affirmation in grim retrospective:

The man on the ground will become their totem.

The boy in their midst

will learn this bitterness in his stomach

is something he can live with

and might even learn to like.

Who else but a lifeguard at a pool can circumvent tragedy, after all, or has even a smidgen of control?

These are the limits we place around our grief, making a monument out of senseless tragedy, even as we’re helpless to change anything.

And what could ever be more hopelessly, nightmarishly tragic than the accidental drowning of a child? This theme/scenario dominates the middle section. While McCullough’s poems deal with an “actual” drowning, it is not a specific one — more like the idea of a drowning, in a kind of dreamscape infused with helpless panic — the parent’s momentary negligence, the lifeguard’s feckless behavior.

all he recalls of the events before the drowning

is how he walked around the pool asking if anyone

had a pen, how one of the mothers leant him her lipstick,

to write the word WARNING both large and red and how satisfied

he felt

both aroused and indicted. (“What the Lifeguard Wrote”)

McCullough’s poems examine the edges of everyday humanity in the face of the struggles we endure. As Thoreau wrote, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” an observation that is borne out in poem after poem in Panic. In “What Needs to Be Done,” a single woman in her thirties cares for her invalid mother while life passes her by, but for all her desperation, she does not complain:

For now, she knows who she is,

and who she is

is sufficient.

In “Gone a Little Wild,” a girl whose twin sister died in a forklift accident plants a garden in her sister’s memory but lets it go to seed when the town won’t let her put up a memorial plaque. In “The Moment Before Something” a struggling single mom is asked out on a date by her boss, considers her options. With real compassion, McCullough lets us glimpse the secret lives of quietly desperate people as they push their boundaries, test their limits. “...they let themselves go as dumb as cows/so they can survive the pastures they must cross.” (“What the Teacher Said”)

Amen.