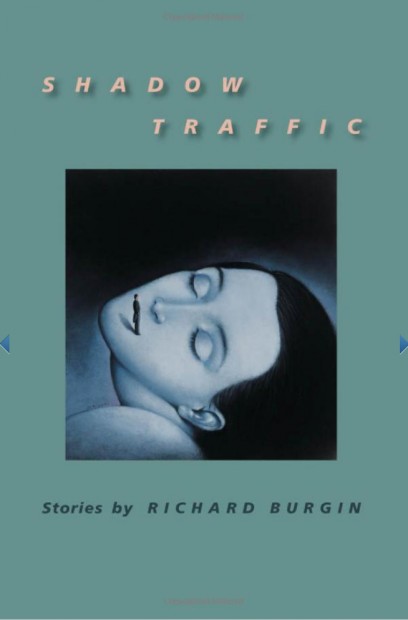

Shadow Traffic

by Richard Burgin

Fiction

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011

$30.00, 267 pages

ISBN: 978-1421402734

Richard Burgin’s fiction is often described as “gritty,” but after reading his latest scintillating collection of stories, I thought perhaps a better descriptor might be “seedy.” In fact, in a collection where the most redemptive story is set in a strip club (“The Dolphin”), “seedy” is perhaps an understatement. This is not by any means a negative pronouncement, mind you-most literary fiction these days seems, to my eyes overly precious or pseudo-lyrical or language-based in a way that sucks all the energy out of the room. Many writers these days seem intent on aping Michael Cunningham, or his ilk (or Pynchon-even worse). Not Burgin. His fiction doesn’t shy from getting down and dirty with the drug dealers and strippers and perverts and gun-wielding men of reprisal.

Richard Burgin's fiction is often described as "gritty," but after reading his latest scintillating collection of stories, I thought perhaps a better descriptor might be "seedy."

Let’s not forget to mention sex directly. Most of Burgin’s stories in this collection deal in some form or fashion with the attempt to get laid—or to get back at someone for not letting them get laid in the way they want to get laid (“Memorial Day,” “Mission Beach,”“Do You Like This Room?”). In other stories there is at least an undertone of sexual menace (“The Dealer,” “Caeser.”) The redemption in this collection usually has to do with bypassing sex in place of something else, though Burgin’s story “The Dealer” includes a circumventing-sex-moment, while still concluding in a kind of fatalistic comeuppance.

“The Dealer” is one of the strongest stories in a strong collection, also because not only does Jeff (the narrator and main character), excuse himself from participating in a threesome with his drug dealer (Dash) and his drug dealer’s “blurry faced” new girlfriend, but because even though this maneuver helps Dash, it leaves Jeff floundering in an increasingly drug-addicted state. Needless to say, both Jeff and Dash are fascinating characters. Not only does Dash deal drugs and mooch from his friends and clients, but he listens to Rush Limbaugh (a faint political jab on the part of the author?). He leads a parasitic existence. Jeff, on the other hand, is so passive and nice that he is in many ways his own worst enemy. He can’t stand up to anyone or anything, and his great heroic moment (nyet on the ménage a trois) is actually just yet another situation where Jeff doesn’t do anything. Jeff simply gives in to his own loneliness (drugs being a mere passage-way to this outcome).

One of the themes I’ve noticed runs throughout most of Burgin’s strong body of work has to do with father-son relationships, or at least surrogate versions of this. “Mission Beach,” another terrific story, has to do with a father bonding with his son over bodysurfing in San Diego. This is not the prototypical Burgin setting, but the maneuver the father makes in the story to consciously continue his bonding session with his son rather than make love to the woman he flirts with is Burginesque in its ruminating quality and ability to take into account the entire context of his life situation—including past relationships. Despite the second person narration (which in the hands of lesser writers is often a distancing effect more than anything), this is one of the sweetest stories in the collection. Here is a quote from the story describing the son, Andy: “He has a strikingly beautiful, blue-eyed face, like one of the children Renoir loved to paint. He’s also extremely smart, funny, very imaginative, and has an exceptional memory.” If it’s possible to be hagiographic about a twelve year old boy, this is the passage that does it.

I wasn’t as fond of the story “Memo and Oblivion” which focuses on a futuristic world which fixates on two drugs (one a memory enhancer and the other which induces forgetfulness). However, this is not Burgin’s fault really; my fiction reading brain isn’t much in tune with speculation, since the current world we live in is, in my view, fascinating fodder enough. Interesting premise, I thought as I read this story-but perhaps at this point I’ve read one too many dystopian novel or seen one too many dystopian films.

However, 99% of this collection clicked on all cylinders for me. Technically speaking Burgin especially excels at dialogue and scene creation/development. At times Burgin’s prose almost has a European flavor (in the Milan Kundera mode)—characters reflect upon Ravel and quote T.S. Eliot. This paradox occurs a lot in the opening story, “Caeser,” for instance. Interesting mix: his fiction is at once seamy and intellectual-a rare comingling. In addition, Burgin really does show rather than tell: this struck me in particular while reading “The Dolphin”—intense story as a result of allowing the scene to play out in front of the reader’s eyes.

Author of fifteen previous books, Richard Burgin keeps pumping out gripping and resilient fiction year after year. Last year’s novel, Rivers Last Longer, was likewise well-written and intense. Read these Burgin books when you have a chance—you will not be disappointed.